If oil and gas production did set off most of Los Angeles’s major earthquakes during the early 20th century, then seismologists may need to recalculate southern California’s rate of natural earthquakes. Hough’s study, however, could still have big implications. In 2015 Oklahoma had nearly a thousand earthquakes of magnitude 3 or greater, up from an average of two per year between 19.

The California and Oklahoma quakes, she says, correspond to totally different mechanisms. That was not done in the early 1900s in California, however, so Hough says the temblors were likely caused just by taking oil and gas out of the ground. In the Midwest today scientists say man-made quakes are largely triggered by injecting wastewater from oil and gas production down into deep disposal wells. Hough also says people should not directly compare the historic earthquakes in California with what is happening in places like Oklahoma and Texas now. “What they showed is that the conditions are such that the earthquakes could well have been triggered by oil pumping activity,” explains David Jackson, professor emeritus of seismology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved with the work. But it is important to note the study does not prove any direct causation. All of these factors, Hough says, provide evidence for a link between the earthquakes and oil and gas activity. In every case oil and gas companies had drilled the wells more than a thousand meters down, which was unusually deep for that time period. Their study, published today in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, explains that the majority of those big earthquakes occurred close to oil wells, often soon after production began. The largest-the 1933 Long Beach earthquake-was magnitude 6.4, killed 120 people and caused $50 million in damage (in 1933 dollars). Hough and Page found that oil and gas production in the Los Angeles Basin may have caused four out of the five major earthquakes in the region during that time.

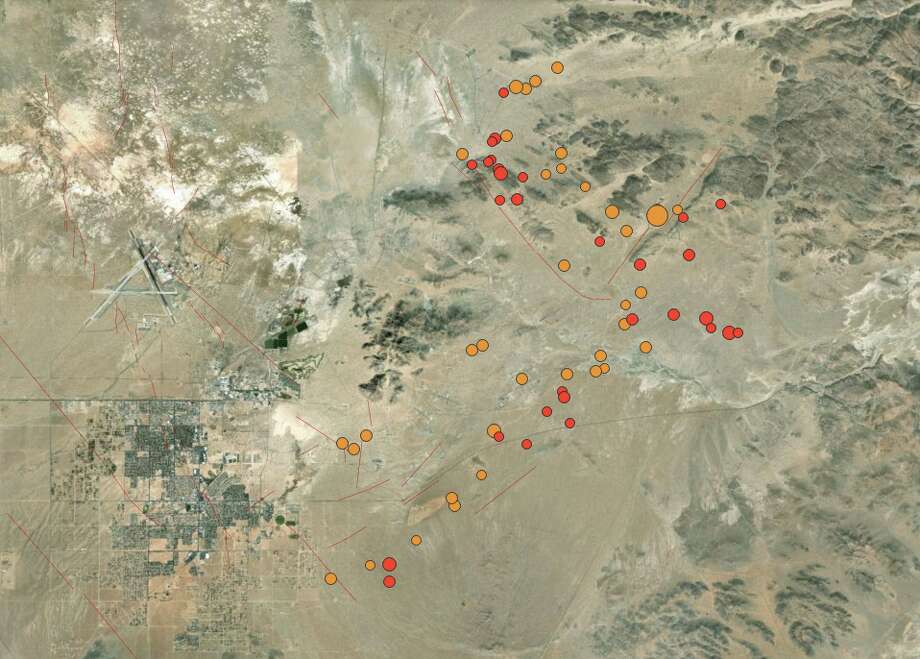

They then analyzed the industry and earthquake data to see if they could establish a connection between the two. The pair also dug through old state reports to get statistics on the oil and gas companies’ production volume, along with locations and depths of their wells. (The largest temblors were the best-documented ones.) Hough and Page restricted their study to this time period because records were spotty prior to 1900, and other researchers had already looked for induced earthquakes in Los Angeles post-1935. They eventually narrowed their investigation to the handful of big, damaging earthquakes that hit the region between 19, during the Los Angeles oil boom. “It’s not as precise as having seismic data, but that doesn’t mean it’s hopeless,” Hough says.įrom those documents, they determined the quakes’ magnitudes, the location of their epicenters and other attributes. Geological Survey relied on a combination of old scientific surveys, crude instrumental data and newspaper accounts to piece together details of quakes in the early 20th century. So researchers Susan Hough and Morgan Page at the U.S. The tools they now use to measure earthquakes were not as sophisticated back then, and historic records are limited. It is challenging enough for scientists to determine whether a modern-day quake is natural or induced, and even more so for one that occurred a hundred years ago. The finding could ultimately change scientists’ predictions for earthquakes in the Los Angeles Basin, and how well they understand man-made, or “induced,” earthquakes around the country. But new work shows some of the biggest temblors might have been caused by oil and gas production, not nature. Southern California suffered a number of big earthquakes in the early 1900s, a pattern that prompted experts to declare the state an earthquake hazard.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)